Contemporary formations

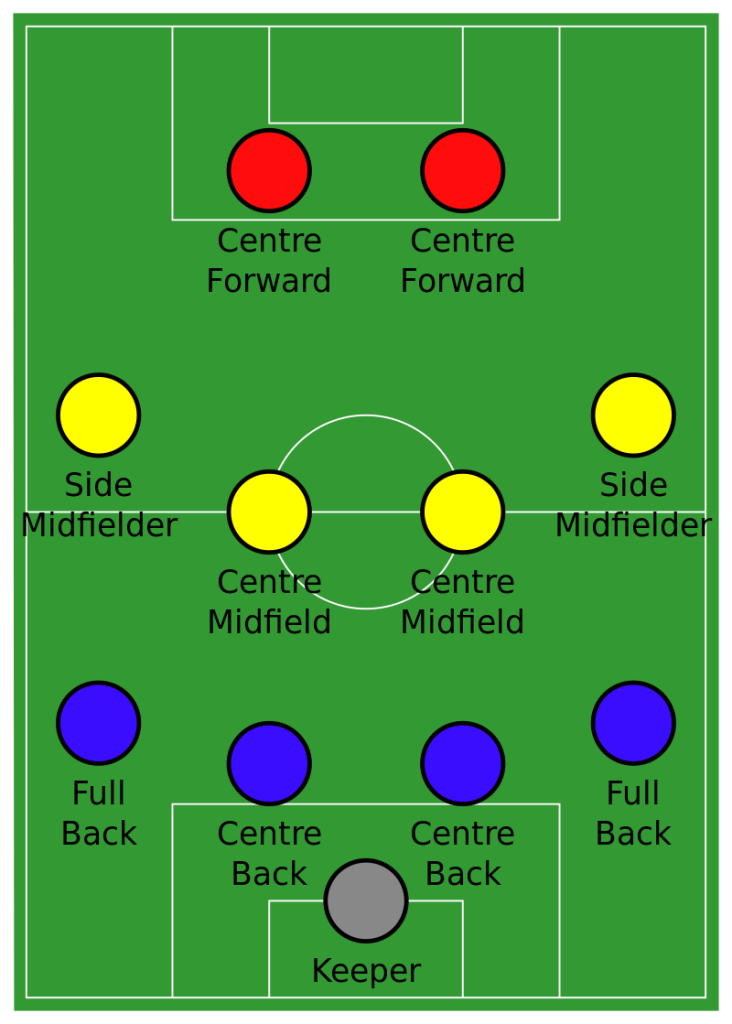

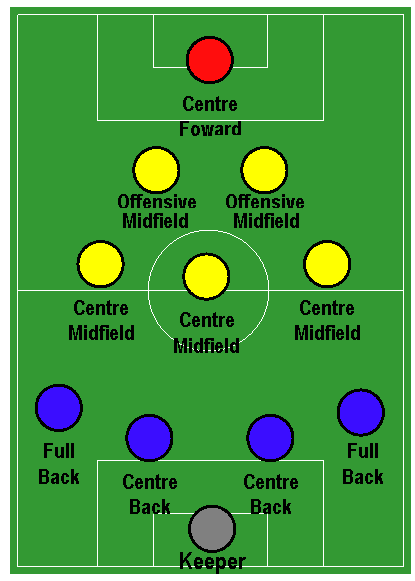

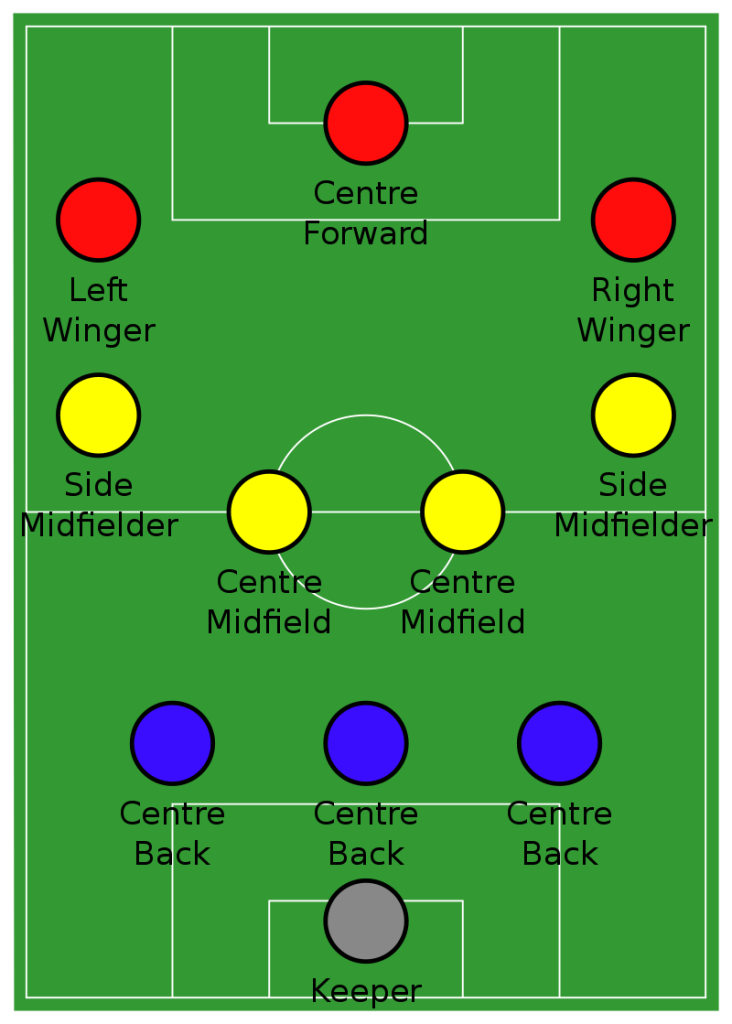

4-4-2

This formation was the most common in football in the 1990s and early 2000s, in which midfielders are required to work hard to support both the defense and the attack: typically one of the central midfielders is expected to go upfield as often as possible to support the forward pair, while the other will play a “holding role”, shielding the defense; the two wide midfield players must move up the flanks to the goal line in attacks and yet also protect the full-backs. On the European level, the major example of a team using a 4–4–2 formation was Milan, trained by Arrigo Sacchi and later Fabio Capello, which won three European Cups, two Intercontinental Cups, and three UEFA Super Cups between 1988 and 1995.

More recently, commentators have noted that at the highest level, the 4–4–2 is being phased out in favor of formations such as the 4–2–3–1. In 2010, none of the winners of the Spanish, English, and Italian leagues, nor the Champions League, relied on the 4–4–2. Following England’s elimination at the 2010 World Cup by a 4–2–3–1 German side, England national team coach Fabio Capello (who was notably successful with the 4–4–2 at Milan in the 1990s) was criticized for playing an “increasingly outdated” 4–4–2 formation.

However, the 4–4–2 is still regarded as the best formation to protect the whole width of the field with the opposing team having to get past two banks of four and has recently had a tactical revival having recently contributed to Diego Simeone’s Atlético Madrid, Carlo Ancelotti’s Real Madrid and Claudio Ranieri’s Leicester City.

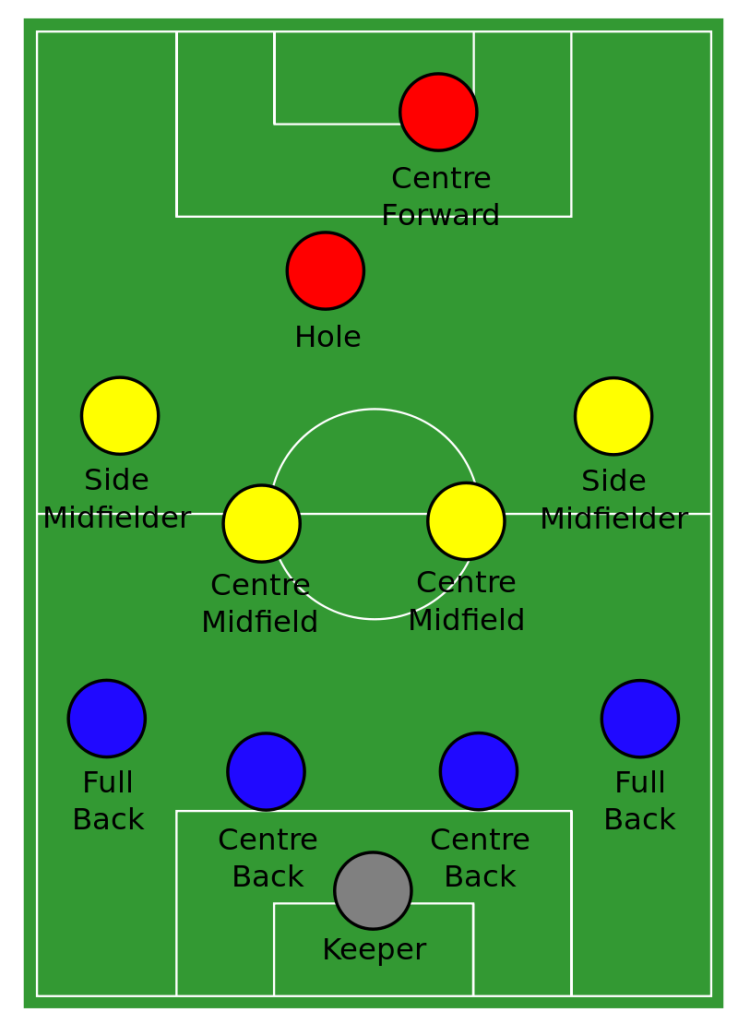

4-4-1-1

A variation of 4–4–2 with one of the strikers playing “in the hole”, or as a “second striker”, slightly behind their partner. The second striker is generally a more creative player, the playmaker, who can drop into midfield to pick up the ball before running with it or passing to teammates. Interpretations of 4–4–1–1 can be slightly muddled, as some might say that the extent to which one forward has dropped off and separated from the other can be debated.

In the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup semi-final match against Germany, United States manager Jill Ellis moved from a traditional 4–4–2 with Abby Wambach and Alex Morgan up top, to a 4–4–1–1 formation replacing Wambach with a withdrawn Carli Lloyd in the hole as a playmaker. The Americans, who had underwhelmed to that point in the tournament, controlled the match for a 2–0 win. The defensive play of Morgan Brian and Lauren Holiday was credited by NBC Sports as unlocking the formation’s attacking potential. The German team’s stronger midfield stretched out of shape to combat the Americans’ wide threats, opening space for Lloyd’s central distribution.

In the 2019 FIFA Women’s World Cup semi-finals, Phil Neville employed the 4–4–1–1 as manager of England against the United States, but deployed right attacker Nikita Parris out of position in the hole and forward Beth Mead also out of position deeper in the midfield. Former Lioness-turned-commentator Eniola Aluko said the tactical shift “failed massively” as the United States scored in the 10th minute and again in the first half, while England struggled to connect play. Despite a reversion to a 4–2–3–1 at the half, the Lionesses lost 2–1.

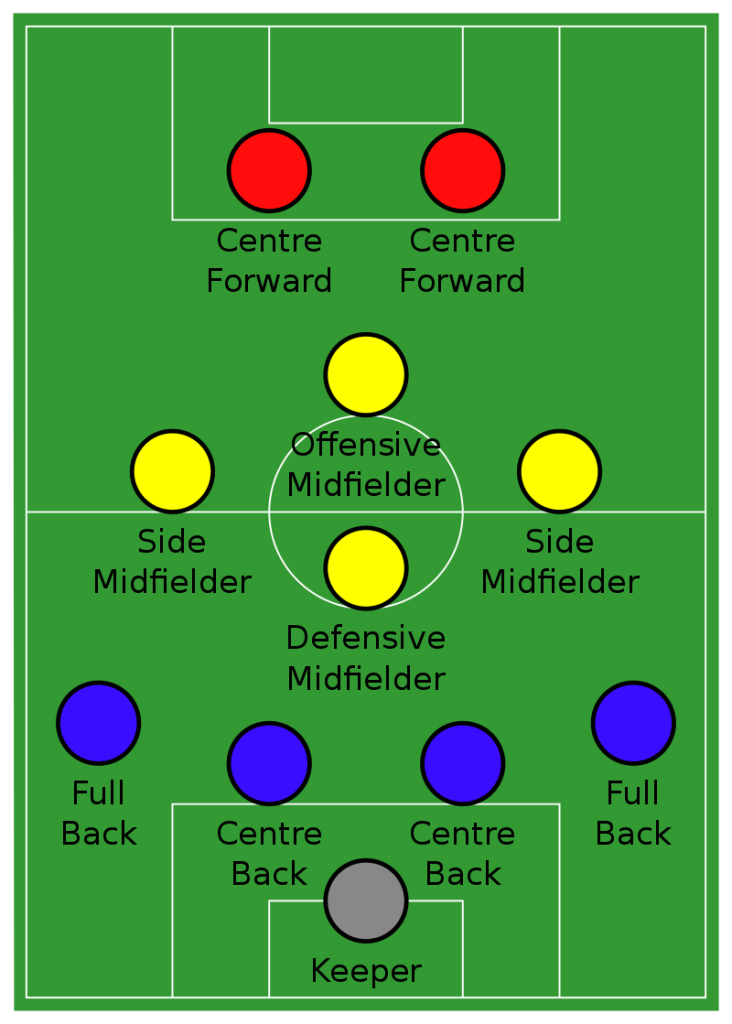

4–4–2 diamond or 4–1–2–1–2

The 4–4–2 diamond (also described as 4–1–2–1–2) staggers the midfield. The width in the team has to come from the full-backs pushing forward. The defensive midfielder is sometimes used as a deep-lying playmaker but needs to remain disciplined and protect the back four behind him. The central attacking midfielder is the creative player, responsible for picking up the ball, and distributing the ball wide to its full-backs or providing the two strikers with through balls. When out of possession, the midfield four must drop and assist the defense, while the two strikers must be free for the counter-attack. Its most famous example was Carlo Ancelotti’s Milan, which won the 2003 UEFA Champions League Final and made Milan runners-up in 2005. Milan was obliged to adopt this formation so as to field talented central midfielder Andrea Pirlo, in a period when the position of offensive midfielder was occupied by Rui Costa and later Kaká. This tactic was gradually abandoned by Milan after Andriy Shevchenko’s departure in 2006, progressively adopting a “Christmas tree” formation.

4–1–3–2

The 4–1–3–2 is a variation of the 4–1–2–1–2 and features a strong and talented defensive centre midfielder. This allows the remaining three midfielders to play further forward and more aggressively and also allows them to pass back to their defensive mid when setting up a play or recovering from a counterattack. The 4–1–3–2 gives a strong presence in the forward middle of the pitch and is considered to be an attacking formation. Opposing teams with fast wingers and strong passing abilities can try to overwhelm the 4–1–3–2 with fast attacks on the wings of the pitch before the three offensive midfielders can fall back to help their defensive line. Valeriy Lobanovskiy is one of the most famous exponents of the formation, using it with Dynamo Kyiv, winning three European trophies in the process. Another example of the 4–1–3–2 in use was the England national team at the 1966 World Cup, managed by Alf Ramsey.

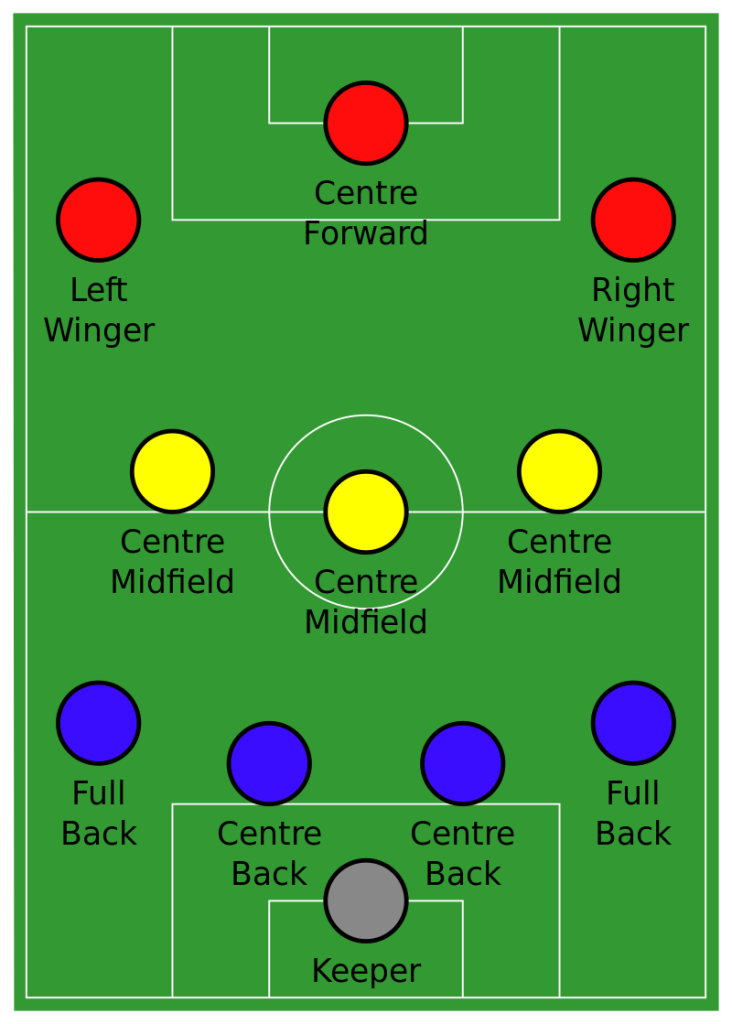

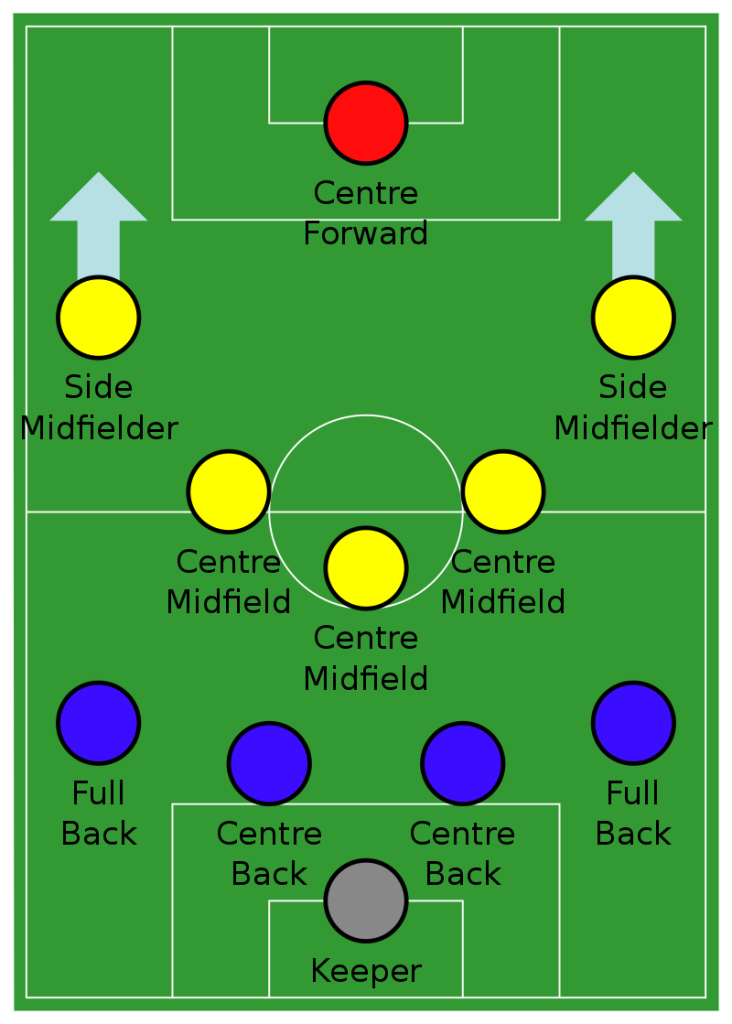

4-3-3

The 4–3–3 was a development of the 4–2–4 and was played by the Brazil national team in the 1962 World Cup, although a 4–3–3 had also previously been used by the Uruguay national team in the 1950 and 1954 World Cups. The extra player in midfield allows a stronger defense, and the midfield could be staggered for different effects. The three midfielders normally play closely together to protect the defense and move laterally across the field as a coordinated unit. The formation is usually played without wide midfielders. The three forwards split across the field to spread the attack and may be expected to mark the opposition full-backs as opposed to doubling back to assist their own full-backs, as do the wide midfielders in a 4–4–2.

A staggered 4–3–3 involving a defensive midfielder (usually numbered four or six) and two attacking midfielders (numbered eight and ten) was commonplace in Italy, Argentina, and Uruguay during the 1960s and 1970s. The Italian variety of 4–3–3 was simply a modification of WM, by converting one of the two wing-halves to a libero (sweeper), whereas the Argentine and Uruguayan formations were derived from 2–3–5 and retained the notional attacking center-half. The national team that made this famous was the Dutch team of the 1974 and 1978 World Cups, even though the team won neither.

In club football, the team that brought this formation to the forefront was the famous Ajax team of the early 1970s, which won three European Cups with Johan Cruyff, and Zdeněk Zeman with Foggia in Italy during the late 1980s, where he completely revitalized the movement supporting this formation. It was also the formation with which Norwegian manager Nils Arne Eggen won 15 Norwegian league titles.

Most teams using this formation now use the specialist defensive midfielder. Recent famous examples include the Porto and Chelsea teams coached by José Mourinho, as well as the Barcelona team under Pep Guardiola. Mourinho has also been credited with bringing this formation to England in his first stint with Chelsea, and it is commonly used by Guardiola’s Manchester City. Liverpool manager Jürgen Klopp is a proponent of the technique, using it to lead the team to victory at the 2018–19 UEFA Champions League final, as well as lifting the 2019–20 Premier League title.

4–3–1–2

A variation of the 4–3–3 wherein a striker gives way to a central attacking midfielder. The formation focuses on the attacking midfielder moving to play through the center with the strikers on either side. It is a much narrower setup in comparison to the 4–3–3 and is usually dependent on the attacking midfielder to create chances. Examples of sides that won trophies using this formation were the 2002–03 UEFA Cup and 2003–04 UEFA Champions League winners Porto under José Mourinho; the 2002–03 UEFA Champions League and 2003–04 Serie A-winning Milan team, and 2009–10 Premier League winners Chelsea, both managed by Carlo Ancelotti. This formation was also adopted by Massimiliano Allegri for the 2010–11 Serie A title-winning season for Milan. It was also the favored formation of Maurizio Sarri during his time at Empoli between 2012 and 2015, during which time they won promotion to Serie A and subsequently avoided relegation, finishing 15th in the 2014–15 Serie A season.

4–1–2–3

A variation of the 4–3–3 with a defensive midfielder, two central midfielders, and a fluid front three.

4–3–2–1 (the “Christmas tree” formation)

The 4–3–2–1, commonly described as the “Christmas tree” formation, has another forward brought on for a midfielder to play “in the hole”, leaving two forwards slightly behind the most forward striker.

Terry Venables and Christian Gross used this formation during their time in charge of Tottenham Hotspur. Since then, the formation has lost its popularity in England. It is, however, most known for being the formation Carlo Ancelotti used on and off during his time as a coach with Milan to lead his team to win the 2007 UEFA Champions League title.

In this approach, the middle of the three central midfielders acts as a playmaker while one of the attacking midfielders plays a free role. However, it is also common for the three midfielders to be energetic shuttlers, providing for the individual talent of the two attacking midfielders ahead. The “Christmas tree” formation is considered a relatively narrow formation and depends on full-backs to provide a presence in wide areas. The formation is also relatively fluid. During open play, one of the side’s central midfielders may drift to the flank to add additional presence.

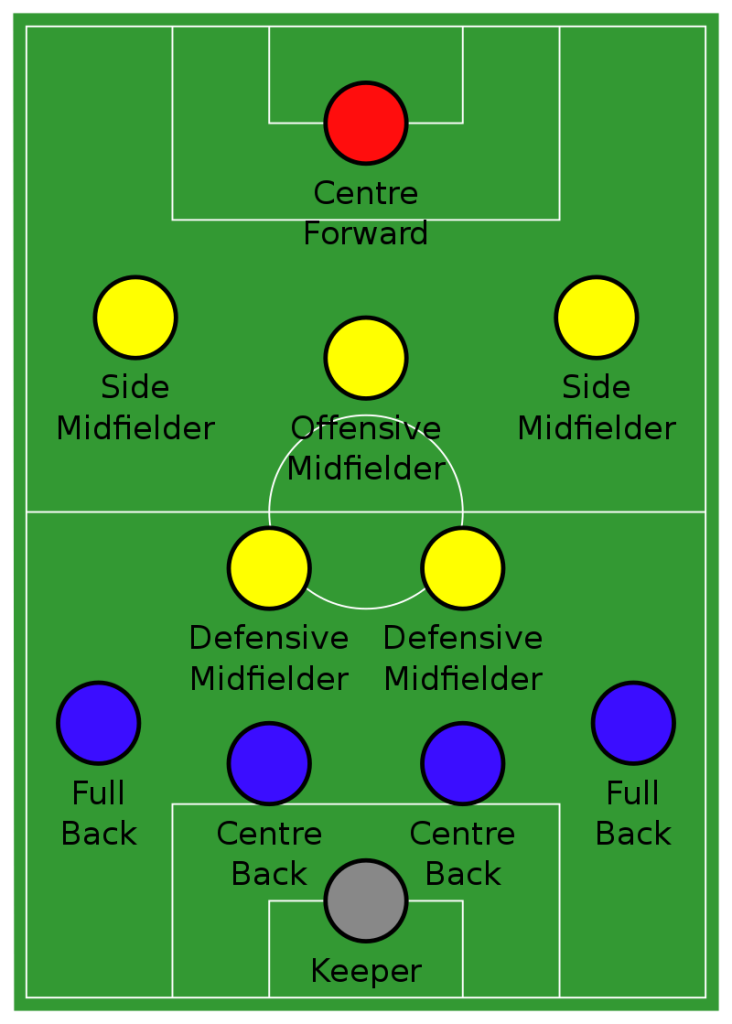

4–2–3–1

A flexible formation in prospects to defensive or offensive orientation, as both the wide players and the full-backs may join the attack. In defense, this formation is similar to either the 4–5–1 or 4–4–1–1. It is used to maintain possession of the ball and stop opponent attacks by controlling the midfield area of the field. The lone striker may be very tall and strong to hold the ball up as his midfielders and full-backs join him in attack. The striker could also be very fast. In these cases, the opponent’s defense will be forced to fall back early, thereby leaving space for the offensive central midfielder. This formation is used especially when a playmaker is to be highlighted. The variations of personnel used on the flanks in this set-up include using traditional wingers, using inverted wingers, or simply using wide midfielders. Different teams and managers have different interpretations of the 4–2–3–1, but one common factor among them all is the presence of the double pivot. The double pivot is the usage of two holding midfielders in front of the defense.

At the international level, this formation is used by the Belgian, French, Dutch, and German national teams in an asymmetric shape, and often with strikers as wide midfielders or inverted wingers. The formation is also currently used by Brazil as an alternative to the 4–2–4 formation of the late 1950s to 1970. Implemented similarly to how the original 4–2–4 was used back then, the use of this formation in this manner is very offensive, creating a six-man attack and a six-man defense tactical layout. The front four attackers are arranged as a pair of wide forwards and a playmaker forward who plays in support of a lone striker. Mário Zagallo also considers the Brazil 1970 football team he coached as pioneers of 4–2–3–1.

In recent[when?] years, with full-backs having ever more increasing attacking roles, the wide players (be they deep lying forwards, inverted wingers, attacking wide midfielders) have been tasked with the defensive responsibility to track and pin down the opposition full-backs. Manuel Pellegrini is an avid proponent of this formation, and frequently uses it in the football clubs that he manages.

This formation has been very frequently used by managers all over the world in the modern game. One particularly effective use of it was Liverpool under Rafael Benítez, who deployed Javier Mascherano, Xabi Alonso, and Steven Gerrard in central midfield, with Gerrard acting in a more advanced role in order to link up with Fernando Torres, who acted as the central striker. Another notable example at club level is Bayern Munich under Jupp Heynckes at his treble-clinching 2012–13 season. Mauricio Pochettino also uses this formation.

4–2–2–2 (magic rectangle)

Often referred to as the “magic rectangle” or “magic square”, this formation was used by France under Michel Hidalgo at the 1982 World Cup and Euro 1984, and later by Henri Michel at the 1986 World Cup and a whole generation, for Brazil with Telê Santana, Carlos Alberto Parreira and Vanderlei Luxemburgo, by Arturo Salah and Francisco Maturana in Colombia. The “Magic Rectangle” is formed by combining two box-to-box midfielders with two deep-lying (“hanging”) forwards across the midfield. This provides a balance in the distribution of possible moves and adds a dynamic quality to midfield play.

This formation was used by former Real Madrid manager Manuel Pellegrini and met with considerable praise. Pellegrini also used this formation while with Villarreal and Málaga. The formation is closely related to a 4–2–4 previously used by Fernando Riera, Pellegrini’s mentor, and that can be traced back to Chile in 1962 who (may have) adopted it from the Frenchman Albert Batteux at the Stade de Reims of the 50s.

The 4–2–2–2 with a box midfield was deployed by the North Carolina Courage of the NWSL from 2017 to 2021, using a front four with the freedom to fluidly switch sides and move wide while served by high-playing fullbacks. The Courage won the league in three consecutive seasons using the formation and the NWSL playoff championship twice, setting season records in wins, points, and goals scored in the process.

This formation had been previously used at Real Madrid by Vanderlei Luxemburgo during his failed stint at the club during the latter part of the 2004–05 season and throughout the 2005–06 season. This formation has been described as being “deeply flawed” and “suicidal”. Luxemburgo is not the only one to use this although it had been used earlier by Brazil in the early 1980s. At first, Telê Santana, then Carlos Alberto Parreira, and Vanderlei Luxemburgo proposed basing the “magic rectangle” on the work of the wing-backs. The rectangle becomes a 3–4–3 on the attack because one of the wing-backs moves downfield.

In another sense, the Colombian 4–2–2–2 is closely related to the 4–4–2 diamond of Brazil, with a style different from the French-Chilean trend and is based on the complementation of a box-to-box with 10 classic. It emphasizes triangulation, especially in the surprise of attack. The 4–2–2–2 formation consists of the standard defensive four (right back, two center backs, and left back), with two center midfielders, two support strikers, and two out-and-out strikers. Similar to the 4–6–0, the formation requires a particularly alert and mobile front four to function. The formation has also been used on occasion by the Brazil national team, notably in the 1998 World Cup final.

4–2–1–3

The somewhat unconventional 4–2–1–3 formation was developed by José Mourinho during his time at Inter Milan, including in the 2010 UEFA Champions League Final. By using captain Javier Zanetti and Esteban Cambiasso in holding midfield positions, he was able to push more players to attack. Wesley Sneijder filled the attacking midfield role and the front three operated as three strikers, rather than having a striker and one player on each wing. Using this formation, Mourinho won The Treble with Inter in only his second season in charge of the club.

As the system becomes more developed and flexible, small groups can be identified to work together in more efficient ways by giving them more specific and different roles within the same lines, and numbers like 4–2–1–3, 4–1–2–3 and even 4–2–2–2 occur.

Many of the current systems have three different formations in each third, defending, middle, and attacking. The goal is to outnumber the other team in all parts of the field but to not completely wear out all the players on the team using it before the full ninety minutes are up. So the one single number is confusing as it may not actually look like a 4–2–1–3 when a team is defending or trying to gain possession. In a positive attack, it may look exactly like a 4–2–1–3.

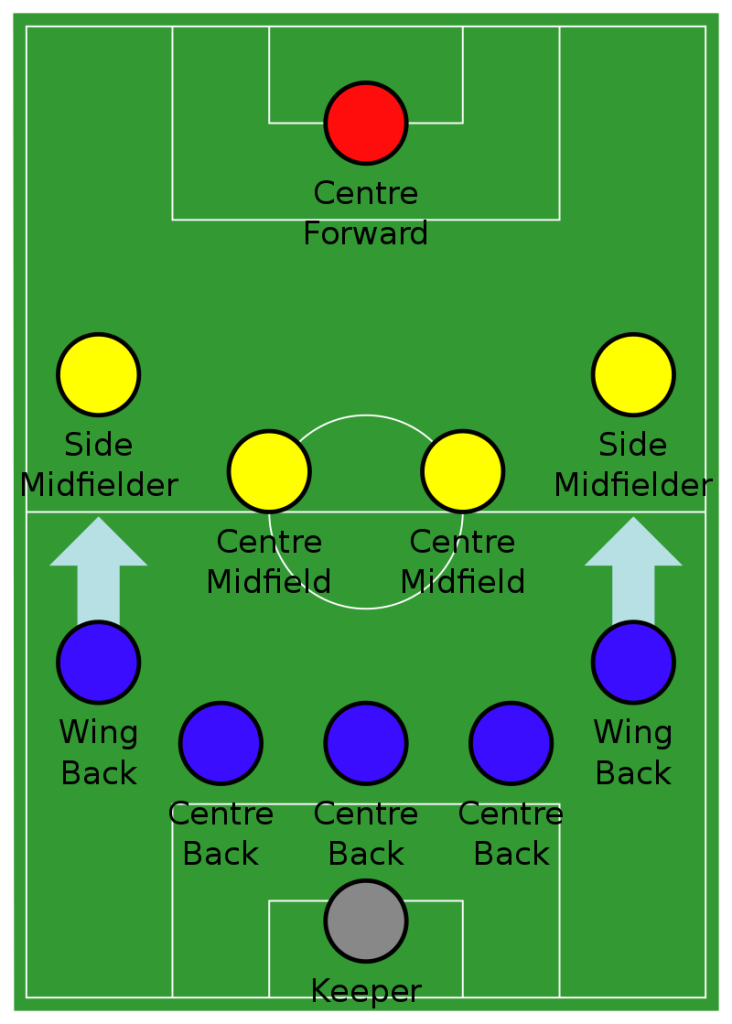

4–5–1

4–5–1 is a conservative formation; however, if the two midfield wingers play a more attacking role, it can be likened to 4–3–3. The formation can be used to grind out 0–0 draws or preserve a lead, as the packing of the center midfield makes it difficult for the opposition to build up play. Because of the “closeness” of the midfield, the opposing team’s forwards will often be starved of possession. Due to the lone striker, however, the center of the midfield does have the responsibility of pushing forward as well. The defensive midfielder will often control the pace of the game.

4–6–0

A highly unconventional formation, the 4–6–0 is an evolution of the 4–2–3–1 or 4–3–3 in which the center forward is exchanged for a player who normally plays as a trequartista (that is, in the “hole”). Suggested as a possible formation for the future of football, the formation sacrifices an out-and-out striker for the tactical advantage of a mobile front four attacking from a position that the opposition defenders cannot mark without being pulled out of position. Because of the intelligence and pace required by the front four attackers to create and attack any space left by the opposition defenders, however, the formation requires a very skillful and well-drilled front four. Due to these demanding requirements from the attackers, and the novelty of playing without a proper goalscorer, the formation has been adopted by very few teams, and rarely consistently. As with the development of many formations, the origins and originators are uncertain, but arguably the first reference to a professional team adopting a similar formation is Anghel Iordănescu’s Romania in the 1994 World Cup Round of 16, when Romania won 3–2 against Argentina.

The first team to adopt the formation systematically was Luciano Spalletti’s Roma side during the 2005–06 Serie A season, mostly out of necessity as his “strikerless” formation, and then notably by Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United side that won the Premier League and Champions League in 2007–08. The formation was unsuccessfully used by Craig Levein’s Scotland against Czech Republic to widespread condemnation. At Euro 2012, Spain coach Vicente del Bosque used the 4–6–0 for his side’s 1–1 group stage draw against Italy and their 4–0 win versus Italy in the final of the tournament.

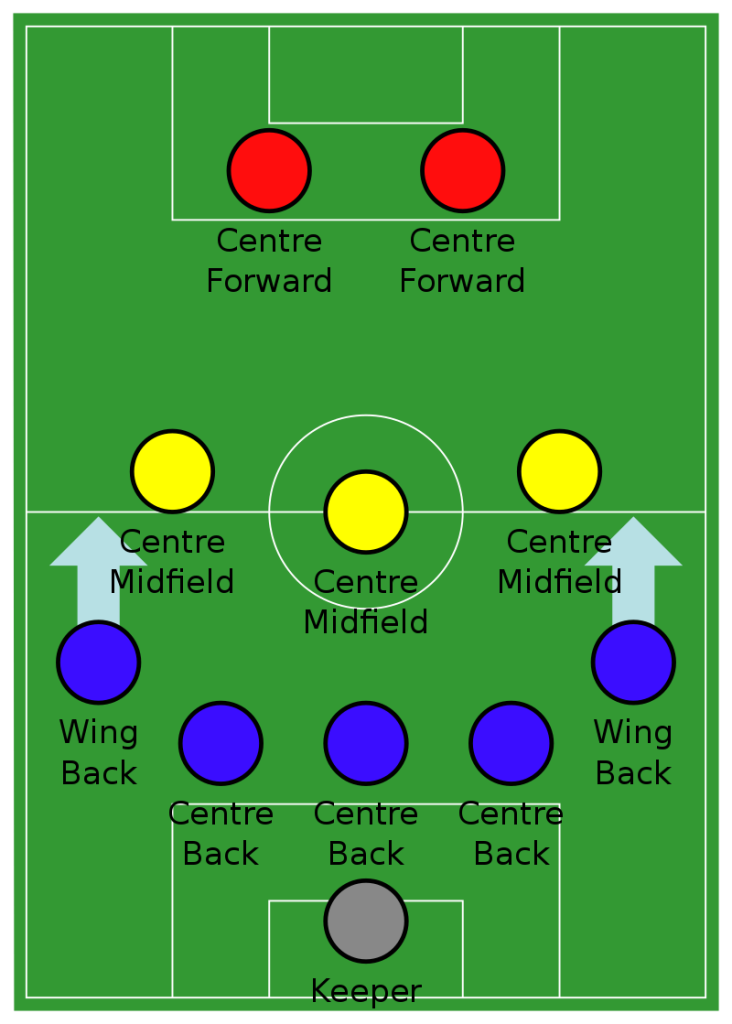

3–4–3

Using a 3–4–3, the midfielders are expected to split their time between attacking and defending. Having only three dedicated defenders means that if the opposing team breaks through the midfield, they will have a greater chance to score than with a more conventional defensive configuration, such as 4–5–1 or 4–4–2. However, the three forwards allow for a greater concentration on attack. This formation is used by more offensive-minded teams. The formation was famously used by Liverpool under Rafael Benítez during the second half of the 2005 UEFA Champions League Final to come back from a three-goal deficit. It was also notably used by Chelsea when they won the Premier League under manager Antonio Conte in the 2016–17 season and when they won the 2021 UEFA Champions League Final under Thomas Tuchel.

Using a 3–4–3, the midfielders are expected to split their time between attacking and defending. Having only three dedicated defenders means that if the opposing team breaks through the midfield, they will have a greater chance to score than with a more conventional defensive configuration, such as 4–5–1 or 4–4–2. However, the three forwards allow for a greater concentration on attack. This formation is used by more offensive-minded teams. The formation was famously used by Liverpool under Rafael Benítez during the second half of the 2005 UEFA Champions League Final to come back from a three-goal deficit. It was also notably used by Chelsea when they won the Premier League under manager Antonio Conte in the 2016–17 season and when they won the 2021 UEFA Champions League Final under Thomas Tuchel.

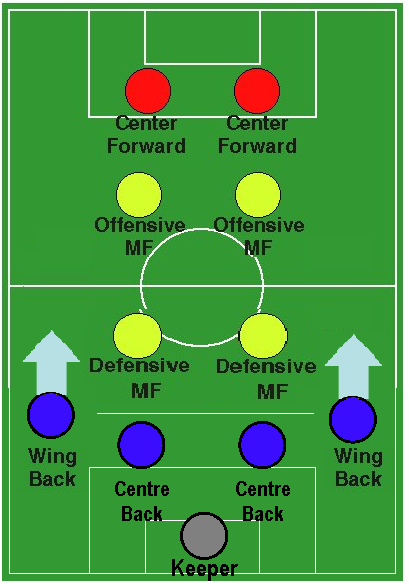

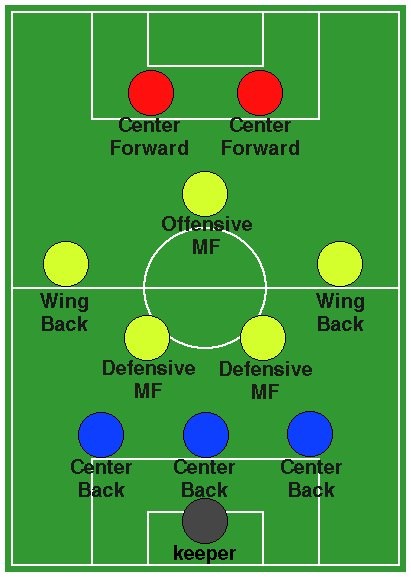

3–5–2

This formation is similar to 5–3–2, but with some important tweaks: there is usually no sweeper (or libero) but rather three classic center-backs, and the two wing-backs are oriented more towards the attack. Because of this, the most central midfielder tends to remain further back in order to help prevent counter-attacks. It also differs from the classical 3–5–2 of the WW by having a non-staggered midfield. There are several coaches claiming to be the inventors of this formation, like two-time European Cup winning manager and World Cup runner-up Ernst Happel and the unorthodox and controversial Nikos Alefantos, but the first to successfully employ it at the highest level was Carlos Bilardo, who led Argentina to win the 1986 World Cup using the 3–5–2. The high point of the 3–5–2’s influence was the 1990 World Cup, with both finalists, Bilardo’s Argentina and Franz Beckenbauer’s West Germany employing it.

In the last years of the first decade of 2000, Gian Piero Gasperini during his years at Genoa CFC (and later in Atalanta BC) used this tactical system, in a modern way, with high pressure, speed, strength, on one defense, and ball possession helped his revival. Later, also, Italian coach Antonio Conte successfully implemented the 3–5–2 at Juventus, having won three Serie A consecutive titles between 2012 and 2014, the first unbeaten (record in a league championship with 20 contestants) and the last reaching the points record (102). After coaching the Italy national team, Conte used the 3–5–2 system at Chelsea during the 2016–17 Premier League season, leading the club to the league title and an FA Cup final. In order to properly counteract the additional forward pressure from the wing-backs in the system, other sides, including Ronald Koeman’s Everton and Mauricio Pochettino’s Tottenham, also used the formation against Chelsea. At the international level, Louis van Gaal utilized a 3–5–2 with the Netherlands in the 2014 World Cup, in which they finished third. Notably, this formation was specifically employed as a counter to the challenge of possession football used by the Spanish national side. Cesare Prandelli used it for Italy’s 1–1 draw with Spain in the group stage of Euro 2012, with some commentators seeing Daniele De Rossi as a sweeper. The Netherlands used it to greater effect against Spain during the group stage of the 2014 World Cup, completing a 5–1 win. This minimized the Dutch weaknesses (inexperience in defense) and maximized their strengths (world-class forwards in Robin van Persie and Arjen Robben).

Simone Inzaghi, who succeeded Antonio Conte at Inter, has helped modernize and further innovate the 3-5-2. Inzaghi’s system builds ball possession through the goalkeeper and defenders and uses midfielders who are quick technical and capable of defending very well. Particularly innovative was his use of side midfielders, called “Quinti” in Italian (“fifths” in English) such as Federico Dimarco. Dimarco was used in a very flexible way with defensive duties in the non-possession phase (playing in the defensive line in a 5-3-2 shape), but would shift in the offensive phase. The two midfield sidemen would go up on the line of the attackers forming a four-man attack in a 3-3-4 shape. In two seasons Inter managed to win four trophies (two Italian supercups and two Italian cups) along with an appearance in the 2023 UEFA Champions League final.

3–2–4–1

Manager Pep Guardiola used this formation at moments in his time at Manchester City, using one main center-back and two defensive midfield anchors. It begins as a typical 4-2-3-1 formation, but differs in attack, with the left or right half-back sliding into a defensive midfield position, and a defensive midfielder sliding up to create the “4” in midfield.

3–4–1–2

3–4–1–2 is a variant of 3–5–2 where the wingers are more withdrawn in favor of one of the central midfielders being pushed further upfield into the “number 10” playmaker position. Martin O’Neill used this formation during the early years of his reign as Celtic manager, noticeably taking them to the 2003 UEFA Cup Final. Portland Thorns FC used a 3–4–1–2 formation to win the 2017 NWSL championship, withdrawing forward Christine Sinclair into the playmaker role rather than moving a midfielder up. The Thorns transitioned to a 4–2–3–1 in 2018 after opposing teams countered the 3–4–1–2 with a stronger midfield presence.

3–6–1

This uncommon modern formation focuses on ball possession in the midfield. In fact, it is very rare to see it as an initial formation, as it is more useful for maintaining a lead or tie score. Its more common variants are 3–4–2–1 or 3–4–3 diamond, which uses two wing-backs. The lone forward must be tactically gifted, not only because he focuses on scoring but also on assisting with back passes to his teammates. Once the team is leading the game, there is an even stronger tactical focus on ball control, short passes, and running down the clock. On the other hand, when the team is losing, at least one of the playmakers will more frequently play on the edge of the area to add depth to the attack. Steve Sampson (for the United States at the 1998 World Cup) and Guus Hiddink (for Australia at the 2006 World Cup) are two of the few coaches who have used this formation. Hiddink used the 3–3–3–1 formation for the Socceroos as well.

3–3–1–3

The 3–3–1–3 was formed of a modification to the Dutch 4–3–3 system Ajax had developed. Coaches like Louis van Gaal and Johan Cruyff brought it to even further attacking extremes and the system eventually found its way to Barcelona, where players such as Andrés Iniesta and Xavi were reared into 3–3–1–3’s philosophy. It demands intense pressing high up the pitch, especially from the forwards, and also an extremely high defensive line, basically playing the whole game inside the opponent’s half. It requires extreme technical precision and rapid ball circulation since one slip or dispossession can result in a vulnerable counter-attack situation. Cruyff’s variant relied on a flatter and wider midfield, but Van Gaal used an offensive midfielder and midfield diamond to link up with the front three more effectively. Marcelo Bielsa has used the system with some success with Argentina and Chile’s national teams and is currently one of the few high-profile managers to use the system in competition today. Diego Simeone had also tried it occasionally at River Plate.

3–3–3–1

The 3–3–3–1 system is a very attacking formation and its compact nature is ideally suited for midfield domination and ball possession. It means a coach can field more attacking players and add extra strength through the spine of the team. The attacking three are usually two wing-backs or wingers with the central player of the three occupying a central attacking midfield or second striker role behind the centre forward. The midfield three consists of two center midfielders ahead of one central defensive midfielder or alternatively one central midfielder and two defensive midfielders. The defensive three can consist of three center-backs or one center-back with a full-back on either side.

The 3–3–3–1 formation was used by Marcelo Bielsa’s Chile in the 2010 World Cup, with three center-backs paired with two wing-backs and a holding player, although a variation is a practical hourglass, using three wide players, a narrow three, a wide three and a center-forward.

5–3–2

This formation has three central defenders, possibly with one acting as a sweeper. This system merges the winger and full-back positions into the wing-back, whose job it is to work their flank along the full length of the pitch, supporting both the defense and the attack. At the club level, the 5–3–2 was famously employed by Helenio Herrera in his Inter Milan side, influencing many other Italian teams of the era. The Brazil team which won the 2002 FIFA World Cups also employed this formation with their wing-backs Cafu and Roberto Carlos two of the best-known proponents of this position.

5–3–2 with sweeper or 1–4–3–2

A variant of the 5–3–2, this involves a more withdrawn sweeper, who may join the midfield, and more advanced full-backs. The 1990 world champion West German teams were known for employing this tactic under Franz Beckenbauer, with his successor Berti Vogts retaining the scheme with some variations during his tenure.

5–4–1

This is a particularly defensive formation, with an isolated forward and a packed defense. Again, however, a couple of attacking full-backs can make this formation resemble something like a 3–6–1. One of the most famous cases of its use is the Euro 2004-winning Greek national team.

AFC Ajax, a football powerhouse with a legacy of excellence, embodies the beauty of attacking play and youth development. Their commitment to nurturing talent and playing an attractive style of football has garnered global admiration. Ajax’s rich history and contemporary success make them a true force in the footballing world.

Yes, exactly. Ajax has made significant contributions to the development of football.