In association football, the formation of a team refers to the position players take in relation to each other on a pitch. As association football is a fluid and fast-moving game, a player’s position (with the exception of the goalkeeper) in a formation does not define their role as tightly as that of a rugby player, nor are there breaks in play where the players must line up in formation (as in gridiron football). A player’s position in a formation typically defines whether a player has a mostly defensive or attacking role and whether they tend to play centrally or towards one side of the pitch.

Formations are described by three or more numbers in order to denote how many players are in each row of the formation, from the most defensive to the most advanced. For example, the “4–5–1” formation has four defenders, five midfielders, and a single forward. The choice of formation is normally made by a team’s manager or head coach. Different formations can be used depending on whether a team wishes to play more attacking or defensive football, and a team may switch formations between or during games for tactical reasons. Teams may also use different formations for attacking and defending phases of play in the same game.

In the early days of football, most team members would play in attacking roles, whereas modern formations are generally split more evenly between defenders, midfielders, and forwards.

formations are described by categorizing the players (not including the goalkeeper) according to their positioning along (not across) the pitch, with the more defensive players given first. For example, 4–4–2 means four defenders, four midfielders, and two forwards.

Traditionally, those within the same category (for example the four midfielders in a 4–4–2) would generally play as a fairly flat line across the pitch, with those out wide often playing in a slightly more advanced position. In many modern formations, this is not the case, which has led to some analysts splitting the categories into two separate bands, leading to four- or even five-numbered formations. A common example is 4–2–1–3, where the midfielders are split into two defensive and one offensive player; as such, this formation can be considered a type of 4–3–3. An example of a five-numbered formation would be 4–1–2–1–2, where the midfield consists of a defensive midfielder, two central midfielders, and an offensive midfielder; this is sometimes considered to be a kind of 4–4–2 (specifically a 4–4–2 diamond, referring to the lozenge shape formed by the four midfielders).

The numbering system was not present until the 4–2–4 system was developed in the 1950s.

Diagrams in this article use a “goalkeeper at the bottom” convention but initially, it was the opposite. The first numbering systems started with the number 1 for the goalkeeper (top of diagrams) and then defenders from left to right and then to the bottom with the forwards at the end.

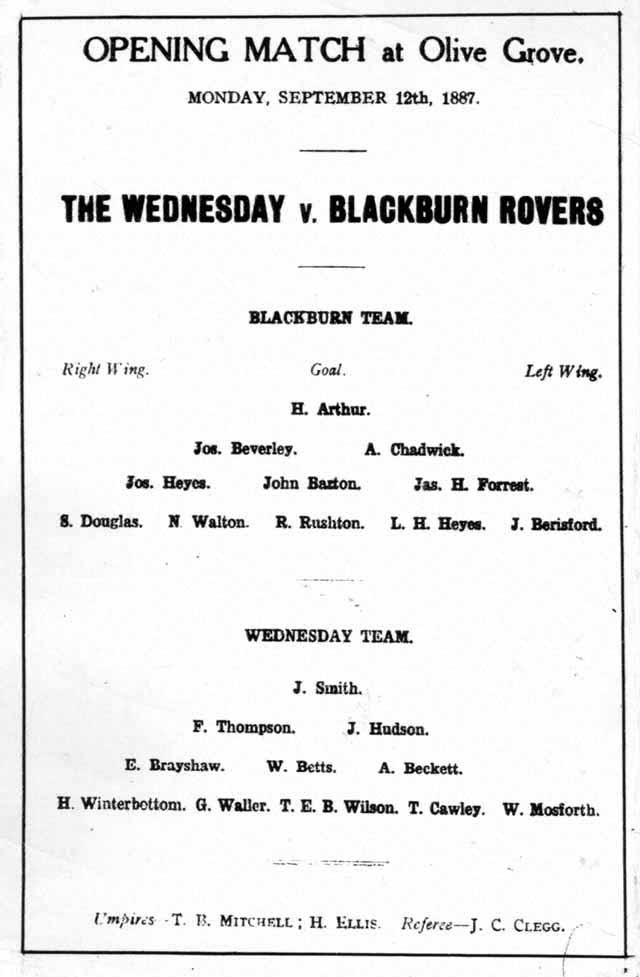

In the football matches of the 19th century, defensive football was not played, and the line-ups reflected the all-attacking nature of these games.

In the first international game, Scotland against England on 30 November 1872, England played with seven or eight forwards in a 1–1–8 or 1–2–7 formation, and Scotland with six, in a 2–2–6 formation. For England, one player would remain in defense, picking up loose balls, and one or two players would hang around midfield and kick the ball upfield for the other players to chase. The English style of play at the time was all about individual excellence and English players were renowned for their dribbling skills. Players would attempt to take the ball forward as far as possible and only when they could proceed no further, would they kick it ahead for someone else to chase. Scotland surprised England by actually passing the ball among players. The Scottish outfield players were organized into pairs and each player would always attempt to pass the ball to his assigned partner. Ironically, with so much attention given to attacking play, the game ended in a 0–0 draw.

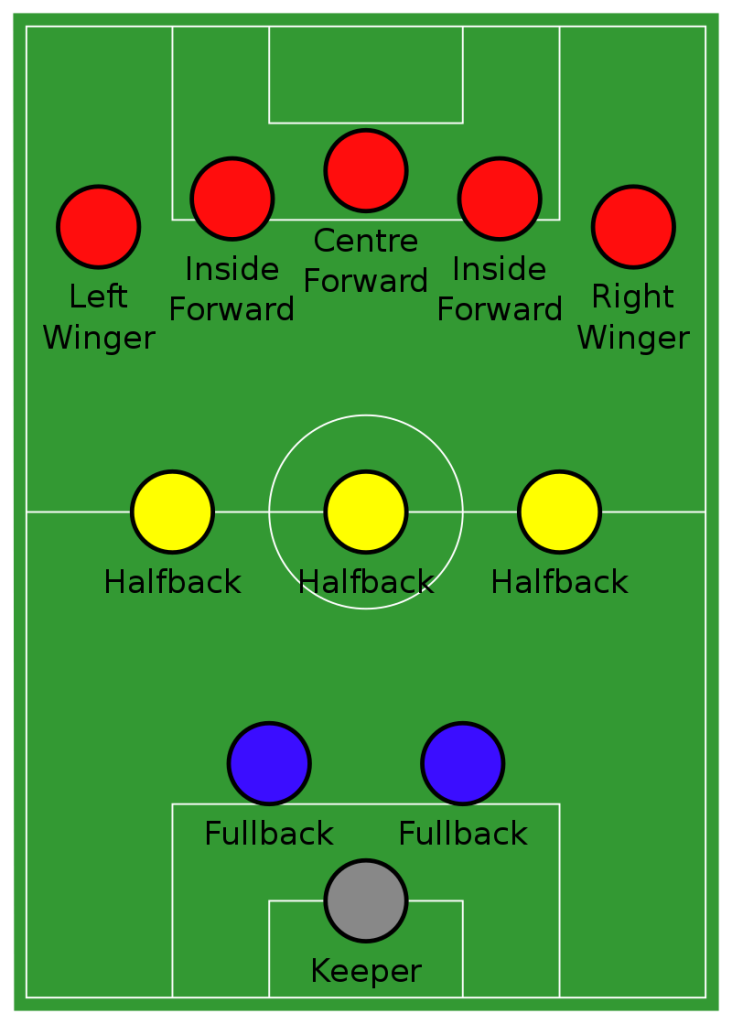

Pyramid (2–3–5)

The first long-term successful formation was recorded in 1880. In Association Football, however, published by Caxton in 1960, the following appears in Vol II, page 432: “Wrexham … the first winner of the Welsh Cup in 1877 … for the first time certainly in Wales and probably in Britain, a team played three half-backs and five forwards …”

The 2–3–5 was originally known as the Pyramid, with the numerical formation being referenced retrospectively. By the 1890s, it was the standard formation in England and had spread all over the world. With some variations, it was used by most top-level teams up to the 1930s.

For the first time, a balance between attacking and defending was reached. When defending, halfback-trio were the first facing opposing forwards, when those were surpassed, then fullbacks met forwards as the last line of defending.

The center halfback had a key role in both helping to organize the team’s attack and marking the opponent’s center forward, supposedly one of their most dangerous players.

This formation was used by the Uruguay national team to win the 1924 and 1928 Olympic Games and also the 1930 FIFA World Cup.

It was this formation that gave rise to the convention of shirt numbers increasing from the back and the right.

Danubian school

The Danubian school of football is a modification of the 2–3–5 formation in which the center forward plays in a more withdrawn position. As played by Austrian, Czechoslovak, and Hungarian teams in the 1920s, it was taken to its peak by the Austrians in the 1930s. It relied on short passing and individual skills. This school was heavily influenced by the likes of Hugo Meisl and Jimmy Hogan, the English coach who visited Austria at the time.

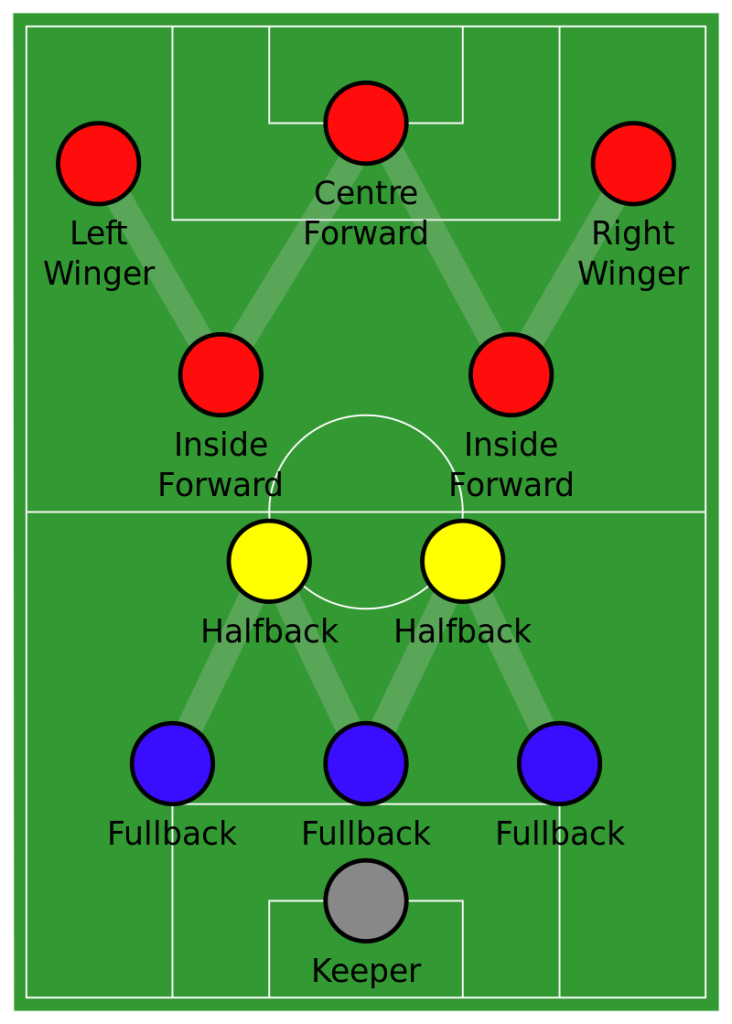

Metodo (2–3–2–3)

The metodo was devised by Vittorio Pozzo, coach of the Italy national team in the 1930s. It was a derivation of the Danubian school. The system was based on the 2–3–5 formation; Pozzo realized that his half-backs would need some more support in order to be superior to the opponent’s midfield, so he pulled two of the forwards to just in front of the midfield, creating a 2–3–2–3 formation. This created a stronger defense than previous systems, as well as allowed effective counter-attacks. The Italy national team won back-to-back World Cups, in 1934 and 1938, using this system. It has been argued that Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona and Bayern Munich used a modern version of this formation.[5] This formation is also similar to the standard in table football, featuring two defenders, five midfielders, and three strikers (which cannot be altered as the “players” are mounted on axles). It can be called MM (if the goalkeeper is at the top of the diagram) or WW (if the goalkeeper is at the bottom).

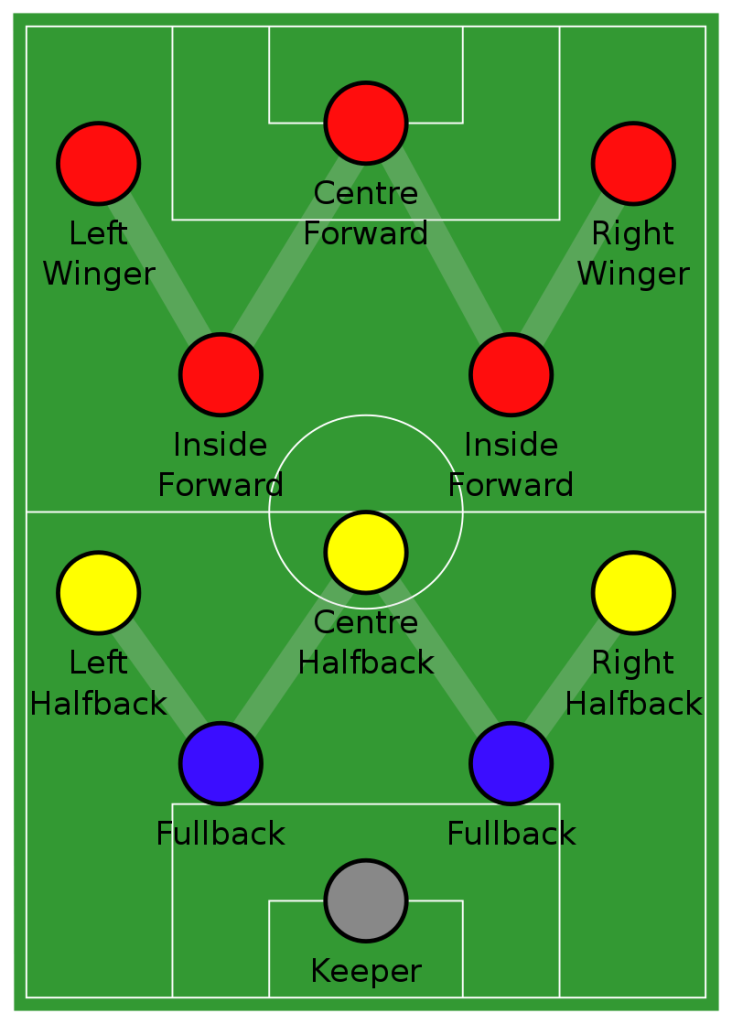

WM

The WM formation, named after the letters resembled by the positions of the players on its diagram, was created in the mid-1920s by Herbert Chapman of Arsenal to counter a change in the offside law in 1925. The change had reduced the number of opposition players that attackers needed between themselves and the goal line from three to two. This led to the introduction of a center-back to stop the opposing center-forward and try to balance defensive and offensive playing. The formation became so successful that by the late 1930s, most English clubs had adopted the WM. Retrospectively, the WM has either been described as a 3–2–5 or as a 3–4–3, or more precisely a 3–2–2–3, reflecting the letters which symbolize it. The gap in the center of the formation between the two wing halves and the two inside forwards allowed Arsenal to counter-attack effectively. The WM was subsequently adapted by several English sides, but none could apply it in quite the same way Chapman had. This was mainly due to the comparative rarity of players like Alex James in the English game. He was one of the earliest playmakers in the history of the game, and the hub around which Chapman’s Arsenal revolved. In 2016, new manager Patrick Vieira, a former Arsenal player, brought the WM formation to New York City FC. In Italian football, the WM formation was known as the Sistema, and its use in Italy later led to the development of the catenaccio formation. The WM formation was used by West Germany during the 1954 FIFA World Cup. It antedates Pozzo’s Metodo and made more radical changes to the widely used system of that era: the 2-3-5 formation.

WW

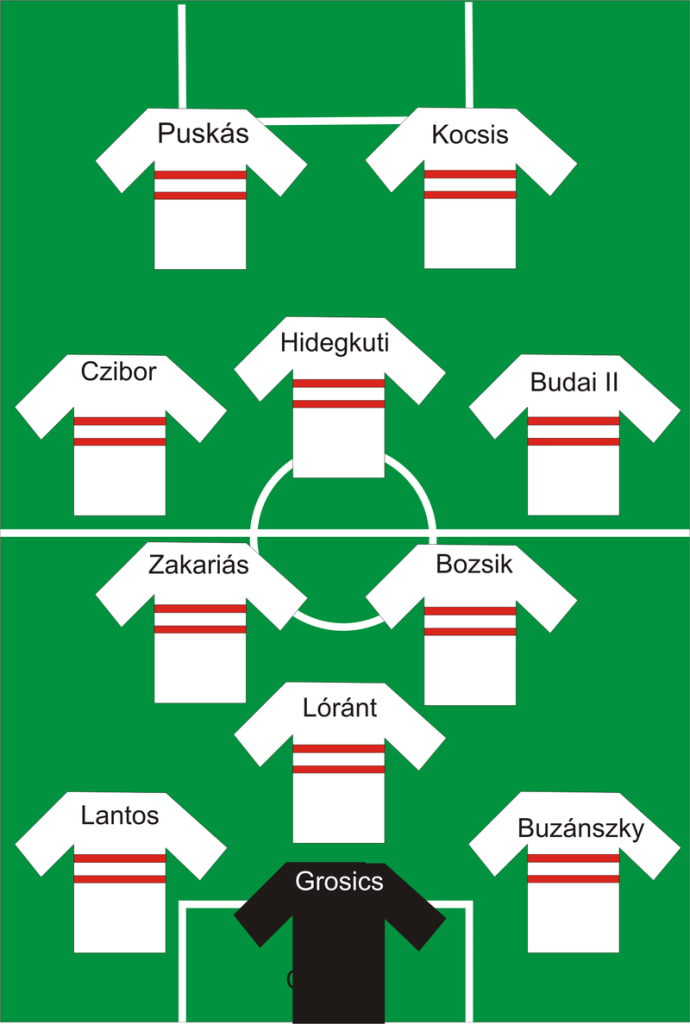

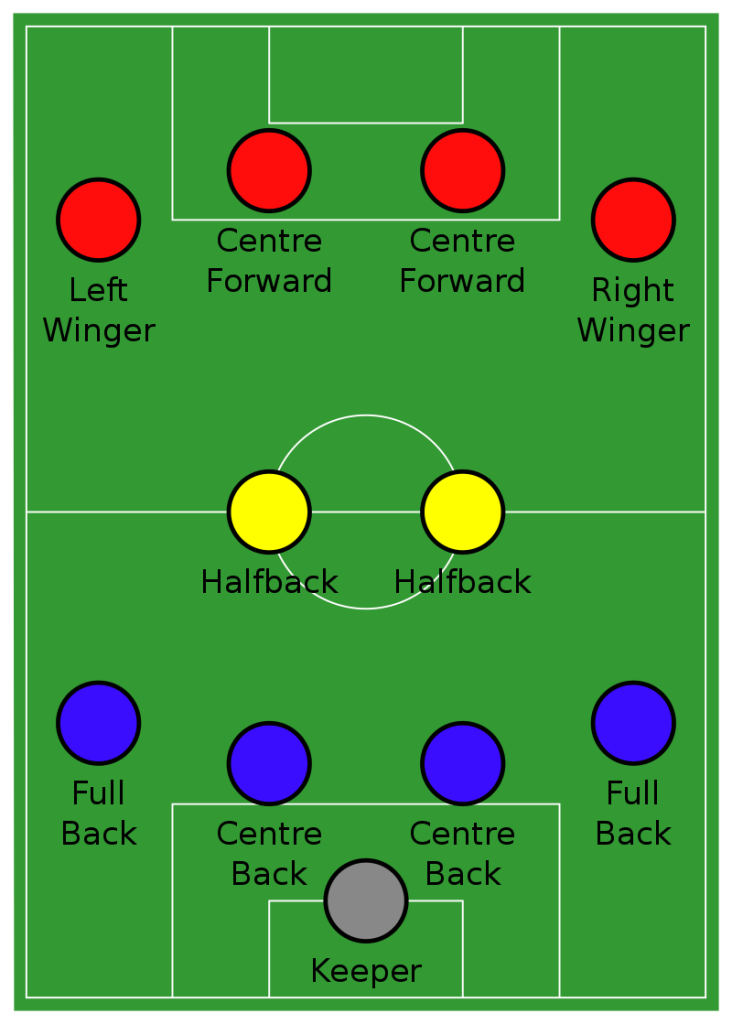

The WW formation (also known as the MM formation, according to the current diagram convention, is the goalkeeper at the bottom. However, it is called the WW formation if the goalkeeper is depicted at the top as was customary at the time), which was a development on the WM formation. It was created by Hungarian Márton Bukovi, who turned the 3–2–2–3/WM formation into a 3–2–3–2 by effectively turning the forward “M” upside down (that is M to W). The lack of an effective center-forward in Bukovi’s team necessitated moving a forward back to midfield to create a playmaker, with another midfielder instructed to focus on defense. This transformed into a 3–2–1–4 formation when attacking and turned back to 3–2–3–2 when possession is lost. This formation has been described by some as somewhat of a genetic link between the WM and 4–2–4 and was also successfully used by Bukovi’s compatriot Gusztáv Sebes for the Hungarian Golden Team in the early 1950s.

3–3–4

The 3–3–4 formation was similar to the WW,[citation needed] with the notable exception of having an inside-forward (as opposed to center-forward) deployed as a midfield schemer alongside the two wing-halves. This formation was commonplace during the 1950s and early 1960s. One of the best exponents of the system was Tottenham Hotspur’s double-winning side of 1961, which deployed a midfield of Danny Blanchflower, John White, and Dave Mackay. Porto won the 2005–06 Primeira Liga using this unusual formation under manager Co Adriaanse.

4-2-4

The 4–2–4 formation attempts to combine a strong attack with a strong defense, and was conceived as a reaction to the WM’s stiffness. It could also be considered a further development of the WW. The 4–2–4 was the first formation to be described using numbers.

While the initial developments leading to the 4–2–4 were devised by Márton Bukovi, the credit for creating the 4–2–4 lies with two people: Flávio Costa, the Brazilian national coach in the early 1950s, as well as another Hungarian, Béla Guttman. These tactics seemed to be developed independently, with the Brazilians discussing these ideas while the Hungarians seemed to be putting them into motion. The fully developed 4–2–4 was only “perfected” in Brazil, however, in the late 1950s.

Costa published his ideas, the “diagonal system”, in the Brazilian newspaper O Cruzeiro, using schematics and, for the first time, the formation description by numbers. The “diagonal system” was another precursor of the 4–2–4 and was created to spur improvisation in players.

Guttmann himself moved to Brazil later in the 1950s to help develop these tactical ideas using the experience of Hungarian coaches.

The 4–2–4 formation made use of the players’ increasing levels of skill and fitness, aiming to effectively use six defenders and six forwards, with the midfielders performing both tasks. The fourth defender increased the number of defensive players but mostly allowed them to be closer together, thus enabling effective cooperation among them, the point being that a stronger defense would allow an even stronger attack.

The relatively empty midfield relied on defenders that should now be able not only to steal the ball but also hold it, pass it or even run with it and start an attack. So this formation required that all players, including defenders, are somehow skillful and with initiative, making it a perfect fit for the Brazilian players’ minds. The 4–2–4 needed a high level of tactical awareness, as having only two midfielders could lead to defensive problems. The system was also fluid enough to allow the formation to change throughout play.

The 4–2–4 was first used with success at the club level in Brazil by Santos, and was used by Brazil in their wins at the 1958 World Cup and 1970 World Cups, both featuring Pelé, and Mário Zagallo, the latter of whom played in 1958 and coached in 1970. The formation was quickly adopted throughout the world after the Brazilian success. Under the management of Jock Stein, Celtic won the 1966–67 European Cup and reached the final of the 1969–70 European Cup using this formation.

It was also used by Vladimír Mirka in Czechoslovakia’s victorious 1968 UEFA European Under-18 Championship campaign. He continued to use it after its waning days.

1–6–3

The 1–6–3 formation was first used by Japan at the behest of General Yoshijirō Umezu in 1936. Famously, Japan defeated the heavily favoured Swedish team 3–2 at the 1936 Olympics with the unorthodox 1–6–3 formation, before going down 0–8 to Italy. The formation was dubbed the “kamikaze” formation sometime in the 1960s when former United States national team player Walter Bahr used it for a limited number of games as coach of the Philadelphia Spartans to garner greater media and fan attention for the struggling franchise.